paraSITE by Michael Rakowitz

Years ago, I came across Michael Rakowitz’s project paraSITE. I thought the idea was interesting: to hook inflatable structures up to air vents and create heated shelters for unsheltered people. In other words, to redirect excess resources to someone in need. Fast-forward, and the parasite reemerges from my subconscious, transformed. My thinking: If you can latch onto a building and redistribute its resources, then why not latch onto a famous institution and redistribute its cultural capital? That’s the core idea behind the parasites artist residency, a punk/DIY approach to redistributing cultural power.

This idea surfaced out of a confluence of needs: academic rejection, artistic ennui, lack of time and headspace to fill out applications and a simple desire to produce work on my own terms, outside of an institutional context. So we decided to try it out and launch a parasite into the art world. We wanted to parasitize an iconic London institution for our first one, so we chose Transport for London (TfL) and called it Alt Art on the Underground. For those of you unfamiliar with TfL, they operate the London public transport system, and they also commission and showcase high profile art under the banner of Art on the Underground.

Parasite 1

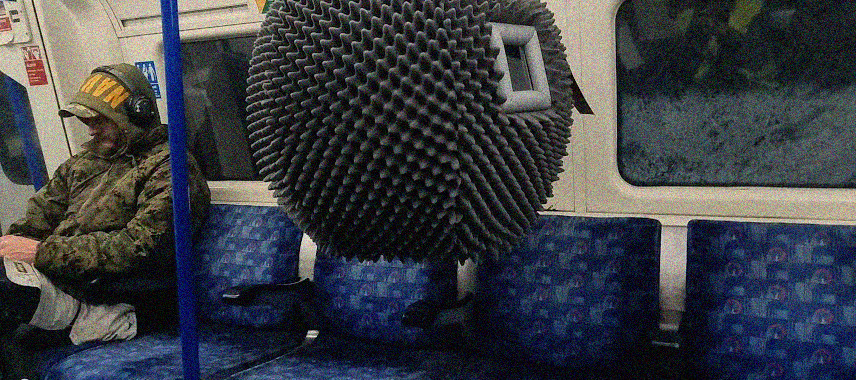

We put out an open call, asking for artists from any practice to respond. The main criteria was that their work in some way challenged and provided generative visions for what public space could be. Our promise was to use the infrastructure of the university where I work for materials and equipment in lieu of access to financial support. We ended up with 12 participating artists, who submitted an array of things from minuscule microbial sculptures, windows into alternate worlds and newly recorded music all the way to a cruise code and a portable sensory deprivation chamber. We wanted to let the TfL system host the artworks, so we made custom hi-vis vests and fake ‘artist in residence’ passes, and spent about six hours installing everything in trains and stations in a piece of durational performance art.

We were treading the threshold of not wanting to be caught (despite being ‘public’ transport, TfL is run by a private company), and wanting a reaction. It was surprising how complacent most of the other passengers were. We were out there during rush hour, and only a few people were curious about what we were up to. Most people just looked tired. Afterwards, I remember thinking that there was an acute lack of freaks on the system. It was depressing but also made me feel like we were necessary.

Afterwards we made a press release (see gallery above) and sent it out via snail mail with samples of the works, including to TfL. We never heard back, but that didn’t really matter. The way I see it, no matter if the host institution or world pays attention, there are potential benefits to participating artists which I’ll elaborate below. Personally, the exercise gave me a frame, and a space in the imagination that helped me create Love Underground, a queer, subversive piece of art – something I almost certainly wouldn’t have made otherwise. And that was a springboard for other things.

Diverted cultural capital: A case study

Since then, I have gotten research funding to develop this project from the institution where I work, which had previously side-eyed my research interests. I was able to channel this funding back into my own creative community by collaborating with a photographer and people from the queer scene to document the project. I also got featured in major publications (Dazed here and Polyester here), exhibited in a group show in London, was part of a queer club night, and was invited to a conference to speak about it and host a panel discussion. It is important to note that the project has outgrown the need for TfL. It is entirely its own thing now. But without the TfL Parasite, none of this would have happened.

So I am wondering if Parasites is a fertile model of subverting hegemonic culture while we can’t escape it, and using it for our own ends. In essence, it lets artists perform cultural capital through another institution (in this case, TfL), feed it back to the host culture (for example, a university), make it pay for its own subversion, and generate and feed counterculture (collaborators, publications, queer nightlife, etc). This is the first time I’ve had time to sit down to write about what it means since we did it. I want to reflect on, and have a conversation with anyone interested, if this is a model worth pursuing, repeating and expanding on.

Evaluation

It seems to me like there are a few things to hold onto here. Let’s start with the cons. They’re pretty obvious.

Accessibility

It would be hard to secure funding for the initial work, since this would kind of defeat the purpose of the exercise. So participation is still precarious and potentially inaccessible to people who do not have the time or resources. Everyone who took part in the inaugural parasite produced work alongside their day jobs. And we accessed as many resources from the university as possible to support everyone.

Quality

By making the residency open to anyone, there is a risk of low quality submissions. There could be a protocol for collective feedback and curation.

Risk

There is risk involved in this parasitic partnership, especially when dealing with powerful private companies. If it comes to hostility, there might be trespassing charges or worse. To keep people safe, we only used initials on the press release and our collective took responsibility for the install.

Co-option

There is potential for the host institution to exploit the artists for clout, especially if this was to become a thing. But publicity would be a win for artists and could give them leverage to steer the conversation.

This is my list of pros.

Ontological Anarchism (after Hakim Bey)

The parasites model creates a Temporary Autonomous Zone (T.A.Z.), first in the collective consciousness of participating artists, and then in the wider world. It carves out a space to create context-specific art without being tied to institutional rules or objectives. This is important, because it provides a spatio-temporal framework and a community for artists who want to make non-commercial/counter-cultural work and have to keep day jobs to stay afloat. Second, it ruptures a complacent space like a rush hour commuter train, by injecting weirdness into consensus reality (or as Mark Fisher might say, capitalist realism) and queering the commonsense use of a space. Like I said, we were the only freaks on the system and imho that made us all the more necessary.

Redistribution of Capital

It flips the script on powerful cultural players exploiting and co-opting sub and countercultures. A core aim of the exercise is to divert the cultural capital of legacy institutions and employ this for the gain of economic, cultural and social capital for participating artists, either immediately, or further down the line. It is a way to short circuit false meritocracy and create access for voices, visions, formats, outputs that are less likely to gain institutional approval before being able to cite previous acceptance by the art world establishment. Redirected streams of capital can also be used to feed counterculture and marginalised creative communities. Overall there is potential to redistribute cultural power and resources, which at (admittedly much larger) scale, could influence goals and outcomes of the wider cultural ecosystem.

A Creative Solidarity Economy

In the current, funding-dependent cultural landscape of post-austerity Britain, the reality is scarcity – with a high number of artists applying for a small number of grants. The parasitic model offers a way to create solidarity and abundance amongst like-minded artists that are less aligned with mainstream funding objectives. This has the potential to create an economy of counter-cultural capital that can be symbiotic within itself, while parasitic to the host culture. The higher the quality of work within the group, the more likely collective furthering of success according to their own metrics and goals.

Countering Censorship

Recently, I have been thinking that, in the face of mounting censorship of artists expressing pro-Palestinian views (such as in Germany) and Arts Council England adding the vague and nefarious caveat to their guidelines that 'overtly political or activist' work might break funding agreements, the parasites model might become useful in new ways too. As an addition to withdrawing work and boycotting, parasitising the institution in question may be an opportunity to create and platform collective critique as a means of generative protest.

I also mentioned that there might be different outcomes and benefits to the way the host culture (meaning the actual institution as well as wider mainstream culture) reacts. Some options are:

Celebrate or acknowledge

The host acknowledges the takeover and potentially platforms it. This scenario is most vulnerable to co-option and re-absorption of the art into mainstream culture. Still, this would be a great option for critical content to make it big and might lead to opportunities for the collective or individual participants.

Ignore or tolerate

This is what happened in our case. There is no platforming or uptake by the host, but the artist can still subvert the host institution’s cultural capital and use it for their own ends. Based on my experience this is a safe and effective middle ground, with the caveat that of course here it is up to the artist to pursue further opportunities.

Condemn or persecute

Benefit: notoriety. All press is good press, right? Just kidding. This scenario is scariest, but could also make the host organisation look very outmoded and decrepit. Clear downsides would be legal action, financial damages, etc.

Conclusion

Overall, I think Parasites is a model that could be expanded on to experiment with new ways to produce counter-hegemonic culture. With some traction, perhaps in a way that big institutions can’t ignore and that creates opportunities for, and solidarity amongst, artists. I am curious to see where it could lead in new iterations, with different host organisations. To me, the parasite also provides an interesting new metaphor and tactics to go with it. I am tired of ‘war’ as a metaphor, whether it’s the ‘culture wars’ or the ‘war on climate change’. A parasite is still a shock to the system, but less fatal. It usually replaces the host’s operating system with its own; transforms it, rather than leaving it dead in the water. Maybe the parasite is one way to wrest back some power and start squirming our way out of a cultural stalemate.

To get wind of the next Parasite, follow us @holobiont.lol. We are planning now and will announce it later this year. To chat about this idea, dm us or get in touch via hello@holobiont.lol.

♥ biont A

Comments